These challenges often stem from the problem of “statelessness”. Statelessness is defined by US Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”) as “having no nationality.” The USCIS definition of nationality requires that one be a national of a “country.” Since the US Department of State does not recognize “Palestine” as a country, Palestinians with no other citizenship or nationality are generally considered stateless. Statelessness has many causes, and other examples of stateless populations across the world include people of Burkinabé descent in Côte d’Ivoire, Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, various populations from the former Soviet Union, and many more.

Statelessness is a serious issue under international law. Many countries systematically deny substantive rights and due process to stateless persons. Stateless persons often have little or no recourse available because they have no home country to return to or to defend them. Palestinians in many countries, especially in the Arab world, are not accorded the same rights as native born citizens, and this leads to countless legal, emotional, and financial hardships.

What does it mean to be stateless in the United States? The US does not have a separate legal framework for stateless persons. On one hand this means that stateless persons do not face systematic discrimination in the US like they may in some countries, but on the other hand it means that there are still irregularities in the law that are often overlooked.

One issue that may cause confusion is the role of passports and travel documents. In general, passports and even other travel documents are proof of a person’s citizenship. This is not the case with Palestinians. Palestinians may carry travel documents from other countries, for example Egypt or Lebanon, or may carry a passport issued by the Palestinian Authority. The US recognizes the validity of both Palestinian passports and travel documents, but only as travel documents, and not as proof of being a citizen or national of a country. That is, a Palestinian who holds a Lebanese travel document is not therefore a citizen of Lebanon. The holder of a Palestinian passport is not therefore a citizen of Palestine. Rather, these persons will generally not be considered by US authorities to have any country of nationality or citizenship. Therefore, a Palestinian visiting or immigrating to the US, even with a Palestinian passport or travel document, will generally still be considered stateless.

Other issues may arise if a stateless person does not have any legal status in the US. A recent case highlighted the difficult situation of a Palestinian asylum seeker who experienced a lengthy detention in the US when his asylum application was denied. The asylum seeker’s legal process became a prolonged dilemma because he did not have a “home country” to be deported to.

Finally, the USCIS and other government agencies do not always have clear guidance in place regarding how to address issues of statelessness on application forms. An experienced immigration attorney can help find the best approach.

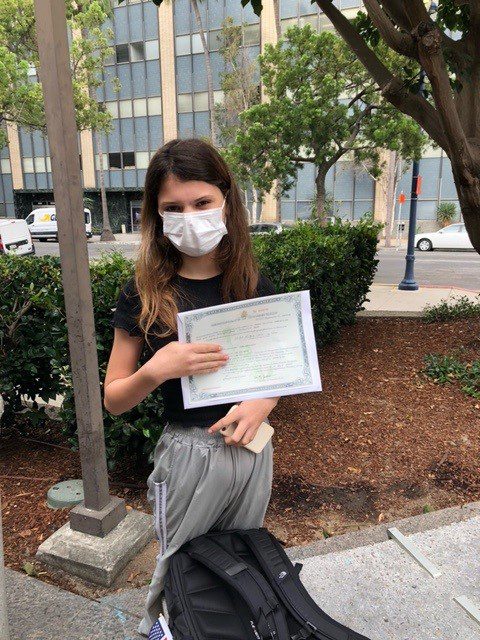

The advantage that the US offers, at least to immigrants, is that after fulfilling the residence requirement, a Lawful Permanent Resident may apply for naturalization. That is, in most cases, if an immigrant lives in the US with a Green Card for five years, even if he is stateless, he may naturalize. In this respect, the US naturalization process offers Palestinian immigrants what is often difficult or impossible for stateless people to obtain: citizenship.

All said and explained in this article does not constitute a legal opinion and does not replace legal advice. Responsibility for using the wordings and opinions conveyed in this article relies solely and entirely on the reader. This article was written by Dotan Cohen Law Offices, working in the field of immigration law in the United States, Canada, Australia and England.